The People Who Don’t Go To Law School, Part 2

The American Bar Association should do a study of people who don’t go to law school, so that we may learn about the ways in which our profession is missing out. What are the talents, ideas, life experiences, and perspectives that never make it down the narrow pathway through law school and into the profession?

The American Bar Association should do a study of people who don’t go to law school, so that we may learn about the ways in which our profession is missing out. What are the talents, ideas, life experiences, and perspectives that never make it down the narrow pathway through law school and into the profession?

I’ve been meeting a remarkable number of people who say that they have seriously contemplated the idea of law school, but for one or a variety of reasons, they ultimately did not go. I previously wrote a short piece speculating about who chooses not go to law school, and my coworker Chris Tittle and I built upon that in a post about diversifying the legal profession. I’m realizing now that this is a subject that could be built upon endlessly. Hence, this is Part 2 of an ongoing inquiry.

Recently, the Sustainable Economies Law Center (SELC) partnered with the National Lawyers Guild, San Francisco Chapter and held a workshop + discussion about legal apprenticeships. At risk of insulting people by guessing their age, I’d estimate that the average age of aspiring lawyers in the room was 40. Much older than most first-year law students, half of whom are under age 25. Many of the attendees reported that they have children. Among them, were:

- An employee of a federal court,

- A paralegal in a law firm,

- An intake coordinator in a law firm,

- A certified court interpreter,

- A librarian,

- A sales manager, and

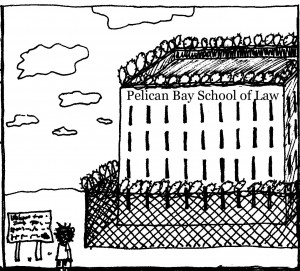

- A friend of someone who has acted as a jailhouse “lawyer” at Pelican Bay State Prison, and who may soon be paroled after 30 years.

It’s worth observing a few things about the people we met that evening:

Workplace Hierarchies: Many of the aspiring lawyers are in a good position to begin an apprenticeship, since they work closely with lawyers or judges. However, most expressed that they are not optimistic about persuading a lawyer to mentor them within their current jobs. This makes me wonder whether law firms rely heavily on the maintenance of hierarchies in the workplace. If a lawyer agrees to mentor a paralegal through the apprenticeship program, the apprentice will eventually become more of an equal. It also implies greater reciprocity in roles – instead of the paralegal simply serving to assist the lawyer, the lawyer now steps into a role of assisting the paralegal through their development as a lawyer. I have to think it would benefit a law firm to maximize everyone’s potential in this way. However, law firms with rigid – and might I add, outmoded – hierarchies may leave little room for such innovation.

Knowledge and Experience: Many of the above listed people have already worked substantially in the legal field and have likely learned quite a bit about the law. Importantly, they also have some of the practical skills and knowledge that law school doesn’t usually teach, such as how to interact skillfully with clients, how to file documents, how to navigate bureaucracies, and how to manage the various functions of a law firm. I learned all of these things precariously and on the fly only after I graduated from law school.

Jailhouse Lawyers: Jailhouse lawyers! One of SELC’s volunteers, Greg Jackson, suggested that criminal defense attorneys could set up offices in prisons and mentor apprentices through the process. This is genius, and an idea worth exploring. With more than 2 million people in U.S. prisons, and public defenders with caseloads exceeding 1000, this could be a way to quickly expand access to necessary legal services and fulfill the mandate of Gideon v. Wainwright. Defense attorneys teaching inmates, inmates providing legal services to inmates, and the cultivation of a strong learning environment in prisons – this is, at least, a step in the direction of justice in a system that needs game-changing solutions.

Jailhouse Lawyers: Jailhouse lawyers! One of SELC’s volunteers, Greg Jackson, suggested that criminal defense attorneys could set up offices in prisons and mentor apprentices through the process. This is genius, and an idea worth exploring. With more than 2 million people in U.S. prisons, and public defenders with caseloads exceeding 1000, this could be a way to quickly expand access to necessary legal services and fulfill the mandate of Gideon v. Wainwright. Defense attorneys teaching inmates, inmates providing legal services to inmates, and the cultivation of a strong learning environment in prisons – this is, at least, a step in the direction of justice in a system that needs game-changing solutions.

Leave a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.